The home of my family in Connecticut has come to be the resting place for many bits and pieces of historical flotsam and jetsam. The archive seems to have assembled itself. I can conjecture why some specific material is present, artifacts passed from one generation to the next, but the origins of much of it is a mystery. Past owners left no record of who is pictured in this daguerreotype or owned these moccasins.

The home of my family in Connecticut has come to be the resting place for many bits and pieces of historical flotsam and jetsam. The archive seems to have assembled itself. I can conjecture why some specific material is present, artifacts passed from one generation to the next, but the origins of much of it is a mystery. Past owners left no record of who is pictured in this daguerreotype or owned these moccasins.

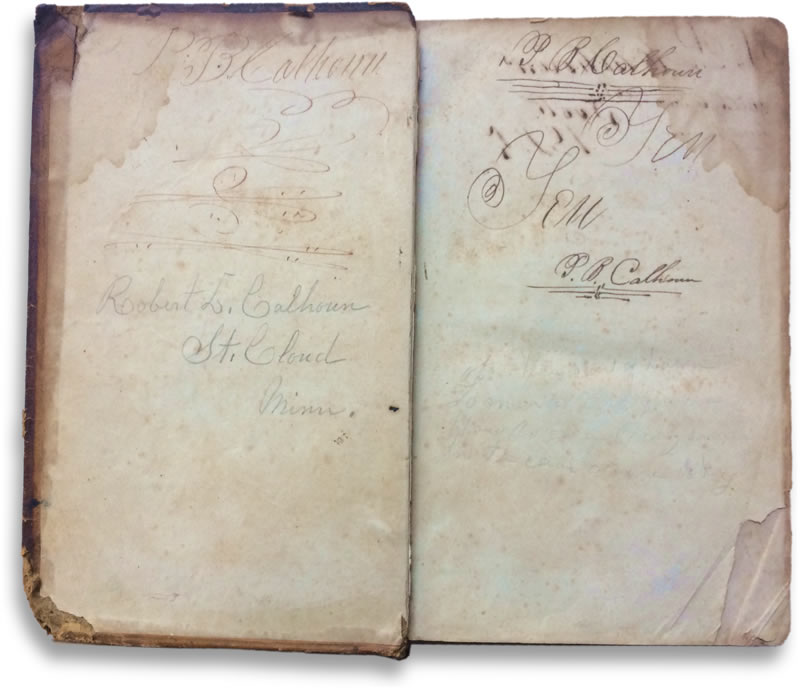

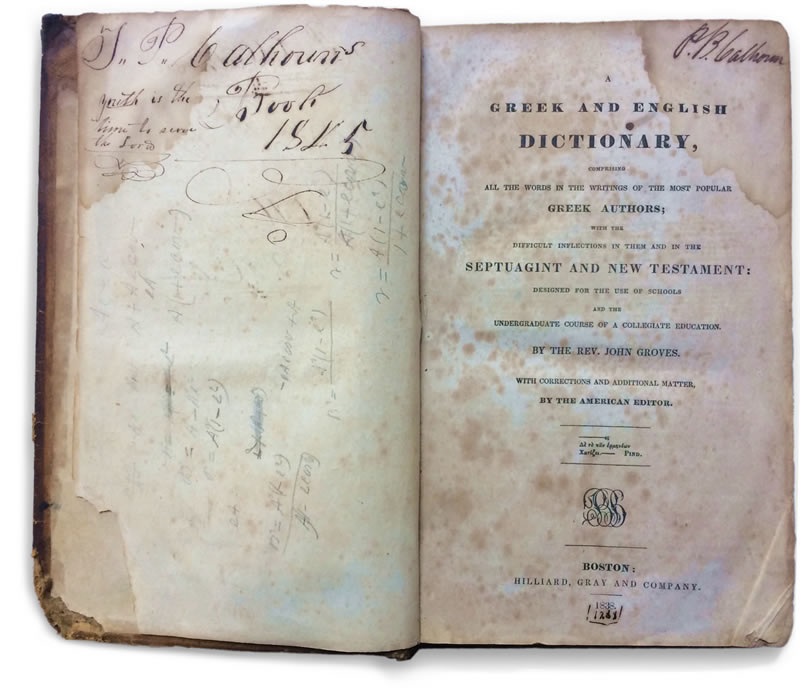

One of my favorite items is A Greek and English dictionary, comprising all the words in the writings of the most popular Greek authors; with the difficult inflections in them and in the Septuagint and New Testament, 1838. This book traveled, hand to hand, from rural Tennessee and Percius Barrett Calhoun (perhaps a gift from his father) to his brother, Thomas P Calhoun, and then to his grandson, Robert L Calhoun, (inscribed in pencil).

Thomas P Calhoun’s inscription gives the year when it came into his possession, 1845, and a reference to Ecclesiastes 12 “Youth is the time to serve the Lord”. There in the Bible is also found “Of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body” to which I cannot add. Benjamin McDonnold wrote in his History of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church that “Thomas Calhoun had a son who entered the ministry. He sent that son to college [Cumberland University] and afterward to a theological school [Andover Theological Seminary]. He nearly all his life was aiding some young preacher to obtain a college education.” The date would suggest that this is a textbook acquired for study at Cumberland and later at Andover. Provenance is otherwise hard to follow since Percius, his next oldest brother who also went to college, moved to Columbus, MS in the 1840s and Thomas P moved to St. Cloud, MN in 1857. Was this Percius’ book first?

![]()

My father's father, Thomas P. Calhoun, and (I have always understood) Thomas's father-in-law, David Lowry, were both Presbyterian ministers. (On pretty circumstantial evidence, I judge they were studious men. I have from my father's shelves a two-volume set of an English translation of Calvin's INSTITUTES with the hand-written inscription: "D. Lowry, Pierce City, Missouri, April, 1878 [?]," and in a very different hand pencilled notes on blank pages at the end of each volume. The book was translated and first published in 1813, and my notion is that the notes were made by David Lowry and the inscription written by someone else, perhaps to indicate the place and date of his death. There is also a four-volume set of Jonathan Edwards's works, published in 1849, with "Thos. P. Calhoun" stamped on the fly-leaf of each volume. The owner of this set contented himself with marginal pencillings and underlinings, but apparently he had read some of the material: including the very tough treatise on the freedom of the will.) — Robert Lowry Calhoun, Family Notes: January 1978

The Cumberland Presbyterian Church broke from the main branch of Presbyterianism in 1810 over differences arising from the revivalist movement. One difference centered on the need for expediency in supplying preachers for new settlements on the frontier. The early church found it necessary to ordain men who possessed an “education without books”.

The Cumberland Presbyterians relaxed the traditional educational standards for the ministry, but were by no means in favor of an "illiterate" clergy, as many of their detractors claimed. Their departure came in de-emphasizing classical studies and concentrating rather on "English grammar, geography, astronomy, natural and moral philosophy, and Church History." Indeed, the Cumberland clergy saw this deviation as only a temporary phenomenon made necessary by the rapid conversion of frontiersmen at the revivals. When the immediate demands for large numbers of ministers could be met, they hoped to return to the classics as the educational foundation of their church. — Street, Thomas P., and Michael D. Green. "Cumberland College in 1829." The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 66, no. 4 (1968): 392-99.

In presbytery minutes from the earliest years a regular item of discussion relates to obtaining an allotment of books for the library. While Cumberland College would not be established for another 15 years, the first ministers sought to establish the foundations of learning from the start. “Calhoon [acquired the] eight volumes of Rollins’s Ancient History”. (We have the 1835 two volume edition in the archive left for us by another ancestor.) Even as the new church found men to speak the gospel, they were not traditional pastors as McDonnold suggests, “In the true sense of the word pastor, there was none in the church till many years later. All the ministers of the second period were missionary evangelists. There is no grander chapter in all church history than the record of these evangelistic tours. Their circuits extended over vast fields, some of them five hundred miles in diameter.”

...the growth of the new settlements and the demands for the gospel kept far ahead of this increase in the supply of ministers. It was folly to talk about settling down into pastorates under these circumstances. Men were called pastors, and they will be so designated in these pages. The name existed, but the reality had no place in all the church till near the close of the second period in this history. Thomas Calhoun is called pastor in the next chapter, but he made frequent tours of evangelism which required six months each. He attended camp-meetings for two or three months every year, and he cultivated a large farm. This system of itinerant missionaries followed the system of circuit riding among the Methodists in some particulars, but differed from it in many others. In theory it was voluntary, but sometimes the pressure on a young man to induce him to take the circuit was very great. With shame be it recorded that many a dear boy has left his half-finished course of studies under this pressure, and gone out "to ride the circuit." Many such, when old men, left in writings, now in my possession, their bitter protests against a policy which robbed them of their education and crippled their life-work. — Benjamin Wilburn McDonnold History of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church (1880)

Years ago, when we moved from a neighborhood near Johns Hopkins University to one near Northwestern University, the bulk of our boxes were filled with books. I could lift one at a time. Our mover would strap three to his back and climb a flight of stairs. He asked in passing, “are you Professors?” He assumed we were because of all the books. That’s our legacy; ancestors who saw the value in keeping a book. There’s always room for one more.

![]()