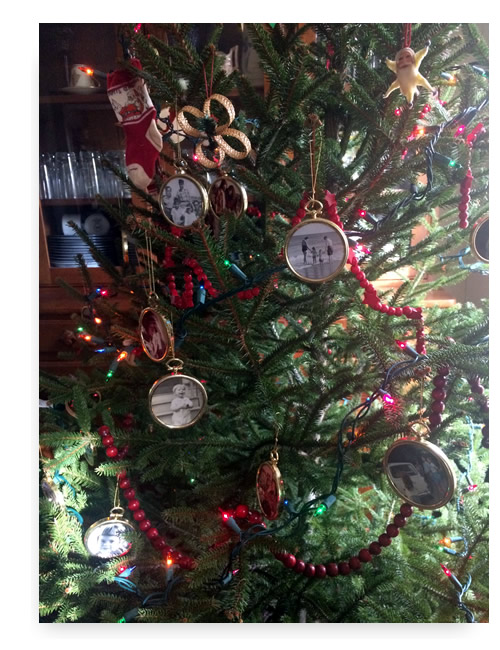

My grandparents, Robert Lowry Calhoun and Ella Clay Wakeman, married on Christmas Eve in 1923. On their 50th wedding anniversary many friends and family came to celebrate. The Christmas tree was hung with photos of several generations. As on the original day we had an iced fruitcake. Years later there was still a piece left in the freezer. I suppose, eventually, someone ate it. 45 years later we also hung the tree with those decorations.

![]() When asked to recount the history of our Calhoun line, my grandfather put together a patchwork of notes on his own memories of his family and some conjectures about more distant ancestry. I keep finding gems in the archive that corroborate the details of his account, e.g., the house in St. Cloud that was his mother’s “special project” seen in a series of photos, interior and exterior, taken soon after it was built. The house is still standing though it has been transfigured with additions, removals and aluminum.

When asked to recount the history of our Calhoun line, my grandfather put together a patchwork of notes on his own memories of his family and some conjectures about more distant ancestry. I keep finding gems in the archive that corroborate the details of his account, e.g., the house in St. Cloud that was his mother’s “special project” seen in a series of photos, interior and exterior, taken soon after it was built. The house is still standing though it has been transfigured with additions, removals and aluminum.

The center section below, which he admits is more “speculative”, is not accurate in it’s suggestions for our most distant ancestors. Like many researching the Calhouns, his facts are mixed with the published genealogies of John Caldwell Calhoun. One such document he had access to is “The Calhoun family of South Carolina” by A. S. Salley that was not available to his father.

![]()

I am glad to have your query about Calhoun forebears, and I will do the best I can with it. Our more remote ancestry I have never seriously tried to disentangle. For better or worse, I have tended to start with the fairly modest situation into which I was born and to go on from there. But I seem to have developed some interest in roots too, and maybe someday I can find out more about our beginnings. Meanwhile, I have two memos, one in my father's handwriting and one in mine, which seem to refer to two different lines of descent; so don't be surprised if things seem blurry from time to time.

My own start, as you know, was at St. Raphael's hospital in St. Cloud, Minnesota, in 1896. My parents were both from the south, my father born in Tennessee in 1853, my mother in Alabama in 1858. They met first while each was visiting relatives in Missouri, and were married in 1886. My one brother was born in 1900, and died during his final year in the Yale School of Medicine in 1927. (He was awarded his M.D. post obit. in June, 1927.)

Now for a mixture of known fact and conjecture, based on the two memos mentioned earlier—my father’s written at some time before 1900 and mine maybe shortly after 1920—sources of both unknown and so of uncertain authority.

My father's father, Thomas P. Calhoun, and (I have always understood) Thomas's father-in-law, David Lowry, were both Presbyterian ministers. (On pretty circumstantial evidence, I judge they were studious men. I have from my father's shelves a two-volume set of an English translation of Calvin's INSTITUTES with the hand-written inscription: "D. Lowry, Pierce City, Missouri, April, 1878 [?]," and in a very different hand pencilled notes on blank pages at the end of each volume. The book was translated and first published in 1813, and my notion is that the notes were made by David Lowry and the inscription written by someone else, perhaps to indicate the place and date of his death. There is also a four-volume set of Jonathan Edwards's works, published in 1849, with "Thos. P. Calhoun" stamped on the fly-leaf of each volume. The owner of this set contented himself with marginal pencillings and underlinings, but apparently he had read some of the material—including the very tough treatise on the freedom of the will.)

My understanding has been that both men went from Tennessee to Minnesota as missionaries, at some time after the birth of my father and a younger sister named Sallie. Central Minnesota was Indian country at that time, with no white settlements of any size. (The federal census of 1850 showed a total population in the territory of 6,077 persons.) Thomas Calhoun and his wife and children settled in the French-named trading post called St. Cloud, where he tried to organize a Presbyterian church. Denominational rules required a minimum of seven adult members, and he never was able to establish a church, though he continued to preach and carry on practical work in the community. One winter day while the children were still small, their parents started in a horse-drawn sleigh to attend a meeting of their little congregation. While they were crossing a wooden bridge over a deep ravine, the horse shied for some unknown reason, and dragged the cutter over the edge into the ravine. My grandfather was killed and his wife seriously but not fatally injured. When she recovered, she took the two children with her to live with relatives in Missouri [I think in Liberty]. (It suddenly occurs to me that if her father, David Lowry, had returned to live in Pierce City, Missouri, she and the children may have joined her father there. I know we had relatives both in Liberty and in Pierce City.) In due course my father, David Thomas Calhoun, had finished his schooling and on June 4, 1874, he graduated in law from Cumberland University in Tennessee, and on the same day, being found "of good moral character and twenty-one years of age," was admitted to practice law. He returned to St. Cloud, and was an active attorney there when on a visit to some Missouri relatives he met Lida Brooks Toomer, at the home of some of her relatives, whom she was visiting from her home in Mobile, Alabama. In the summer of 1886 they were married, and after a hair-raising cruise up the Mississippi—the skippers of two paddle-wheel steamboats decided to have a race, and before it was over were breaking up furniture to stoke their boilers—settled in St. Cloud, in rooms rented from an old-timer named Ellen Lamb.

My mother, born in 1858, was the youngest of nine children. Her oldest brother Edward was twenty-two years older than she, and fought as a captain in Lee's cavalry in the Army of Northern Virginia until the end of the Civil War. (From a visit to Mobile in 1903, I remember him as a tall, gray-bearded, courtly man with a gentle sense of humor and a knack for making a small boy feel important. He lived to be 96.) Mother's earliest years, before the outbreak of war, were spent on her father's plantation somewhere north of Mobile, on or near the Tombigbee River. Her father's name was Benjamin Toomer, a cotton planter of Welsh ancestry. Her mother's name before her marriage was Lucinda Huddleston, with forebears near the Scottish border, in Northumberland. (Ted will remember the picture of Hutton John, where Huddlestons still lived when I was about to come home from Oxford in 1920. The core of the rambling stone house was a "border tower" in a line of similar strongholds, on top of which, I was told, signal fires could be kindled whenever in mediaeval and later times, Scottish raiding parties came over the border into the sheep-raising district around the English lakes.) During the Civil War, when my mother was a girl of five or six, her father's plantation was overrun by marauders, and his stubborn refusal to change his Confederate money before the end of the war left him financially ruined. He started again in the city as a cotton factor, and must have done well, until a dishonest partner incurred debts for the firm, which my grandfather insisted on shouldering as a personal obligation instead of having the debts written off through bankruptcy proceedings. Again he worked his way out of the jam, and continued to keep regular office hours, my mother used to say, until he retired at 82. He died two years later. My grandmother Toomer was still living, with my Uncle Ed, in 1903; a tiny, sparkling lady who lived to be 91.

My mother's happiest years, almost certainly, were those of her growing-up time. She used to speak of her carefree country living now and again: her own horse to ride (side-saddle) every morning before breakfast; her own double-barreled shotgun to carry on quail hunts; her happy-go-lucky teen-age friends who swam in the Tombigbee, leaving a sentry on watch when a water moccasin had been sighted and had holed up in the river bank. On pic-nics there would be prime watermelons in wholesale lots sliced open for the heart, and the rest into the trough for the hogs. She remembered too teaching the children of the field hands to read, and helping to nurse them when they were sick. And she remembered the shock and sorrow in the South when the news came that Lincoln had been shot.

All that easy-going freedom was past when she married my father, and came north to live in strange surroundings and with responsibilities she had never had to cope with before. My father was the sort of lawyer who would spend a hundred dollars preparing a case and send a bill for ten dollars if he thought his client couldn't afford more. (Years later, when I spent three summers working for the Great Northern railroad, some grizzled section hand would ask me now and again: "Your name Calhoun?" Yes. "You any relation to D. T. Calhoun?" Yes; his son. "Well, he was a great man. He won me my case against the G N and wouldn't take nothing for it.") So my mother had to turn business manager: twist his arm until he promised to buy land next to Auntie Lamb's, and build a house for the two of them; ride herd on him and his Lincolnesque partner M. D. Taylor (later chief justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, and still later a tranquil retiree in Berkeley, where in January, 1942, I had dinner with him at his married daughter's home); keep track of the household expenses and, make sure the bills got paid. There were well-to-do families in St. Cloud: families like those of W. B. Mitchell, president of the bank; of A. G. Whitney, head of the local power company (who gave me my first job, at 60 cents a day as time-keeper for a construction crew); of H. L. Ervin, who owned the flour mill. But ours was not one of them. When my father died at 53, after a bout with pneumonia and a massive coronary attack, Mother was left with the house she had schemed and for, and $20,000 worth of life insurance, half of it an annuity that would expire in ten years.

My father was a man with whom I have often wished I had had a chance to get acquainted. Physically he seemed to me enormous: six feet one-and-a-half inches, 230 pounds. He was very deaf when I was old enough to notice, and he was sensitive and embarrassed about his increasing deficiency. (There were, of course, no electronic helps to make things easier.) He had some success in elective politics: at different times city attorney and mayor of St. Cloud, and once he ran unsuccessfully for attorney-general of the state, and lost to Moses Clapp, then the state's Republican boss, though my mother records (on the basis of newspaper reports at the time) that his home County and the adjoining county up-river (Stearns and Morrison counties) his vote included enough Republicans to outstrip his Republican opponent by surprising margins. His last public office was a place as probate judge for Stearns County. His growing deafness made him fear that he could not give satisfactory service in public office, and after he was told by a friendly delegation of Catholic politicians, representing a three-to-one majority of voters in St. Cloud, that they had decided that their man, Herman Bruner, should "have a turn," he never sought election again.

He had turned against the Presbyterian church (which in St. Cloud was one of seventeen Protestant denominations sharing about a fourth of the 8000 townspeople), and found his own spiritual equivalent in Scottish rite Masonry. My mother, who was herself a devoted church member (Southern Methodist in early life, Presbyterian after her marriage—and Congregationalist when after my father's death she moved first to Northfield, Minnesota, and then to West Haven and to New Haven, to be near my brother and me), shared Father's deep interest in the Masonic tradition; and both held various official posts in the corresponding town and state lodges. At the same time—again mainly by reason of increasing deafness and innate shyness—he withdrew more and more from social affairs and felt at home only with two or three very homespun pals—a railway agent, a baggage-master, and a couple more—with whom he could go hunting, play cribbage, or just sit and talk and smoke cigars and occasionally drink beer.

He did his level best to make meaningful contact with my brother Edward and me. When he went to Minneapolis or to Chicago on business, he never failed to bring each of us a gift—toy or book or whatever. But he just could not think and talk in the language of our small world. I started in public school in January, 1904, or thereabout. (Mother had taught me at home to read, spell, and use simple arithmetic, so I was shoved through the first three grades between January and June, and went on in the fourth grade in the fall of 1904.) From time to time some questions would come up in class which a teacher would think my father might help to answer and I always took the question to him with confidence that he would listen. He always did. And he always gave me a careful, not to say painstaking answer, as if he were advising a client; and I never understood what the answer was. He tried, and I tried. We just were in different worlds of discourse.

He died when I was not quite ten years old. What I know about him now has made me grieve many a time over having missed the chance to know him face to face, in his own terms. On his book-shelves were William James's two-volume Principles of Psychology, Varieties of Religious Experience, The Will to Believe and Other Essays, Hugo Munsterberg and Morton Prince on psychology and psychiatry, sets of Elizabethan and Restoration dramatists, Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy, Tennyson, Browning, and other major poets—an astonishing array of reading for a small town lawyer. It is painfully evident that intellectually he was a lonely man. His professional associates were more men of business than of scholarship. Even the minister of our Presbyterian church I learned in due course to know was a stiffened Scotch fundamentalist, arrogant and ignorant, though as a small boy I didn't think in those terms. Mother shared Father's delight in poetry and in Masonic ritual, though not his Intellectual scepticism and questing. She herself had never been to school of any sort: a series of governesses had taught her during her childhood, and she had gone on under her own very real power, and she provided Father support, balance, and reassurance he sorely needed. But his more far-out searching for answers was something quite foreign to her firm Biblical faith. (I have her copy of the King James version of the Bible with a series of dots—eleven of them—after each chapter, to indicate that she had read through it from beginning to end eleven times.) Once I was eighteen and had finished college, with something like a major in philosophy, I could have begun to talk Father's language, and both of us would have found a pleasure we missed because of his death.

Now for some more speculative glimpses into the remoter past. As I noted earlier, I have two memos naming names, one written by my father at some time before 1900, the other in my hand-writing perhaps about 1920. I have no idea what sources either of us used, and the two lists of names and dates do not agree very well—in fact at one crucial point, chronology makes it impossible to parallel them. They almost agree as to the initial immigration to this country. Father's memo read "About the beginning of 2nd quarter of the last century [that is, about 1725], 3 brothers emigrated to America from Ireland. One Patrick was the father of John C. Cal[houn]—another an older brother became the father of John Ewing Calhoun who preceded John C. in U S S [the United States Senate] from S[outh] C[arolina]. From third brother came our family. Samuel Calhoun was the son of _______ Calhoun, from Samuel came Thomas. 3 C. bro's went from Penn to S.C.." My memo indicates "4 brothers—Augusta Co., Virginia, 1746: James, Ezekiel, William, Patrick," and goes on to name the children of each. So far the memos are not incompatible: Virginia could easily have been an intermediate stop between Pennsylvania and South Carolina.

The incompatibility starts with Samuel, obviously a vital figure for our family line of descent. The only Samuel in my list was a grandson of William, one of the original brothers. Samuel's father (a son of William) is listed as Joseph, b. 10/22/1750; M[ember of] C[ongress] 1807—1811; d. Apr.14, 1817." His son Samuel (one of four sons) is listed without dates, and is said to have "died unmarried." Father's memo, very general with respect to the interval between the original brothers and the Samuel he names, becomes very specific at that point: "Samuel C. was born in S.C. about 1740, was a soldier in the Revolution. After the war he removed to N[orth] C[arolina], thence to Tenn. in 1798, settled in Wilson Co[unty] in 1801, where he died in 1833. His wife was Nancy Neeley. She was born in Penn. in 1755, was of Scotch descent and died in Tenn. in 1825. They had [eight children]" one of whom was a Thomas. "Thos Calhoun was born in N.C. May 31, 1782. In 1808 he was married to Miss Mary Robertson Johnston who was born in 1787 in N.C. Her father Alexander Johnson [sic] was born in the same state about 1760, was of Welsh descent, and died in 1800. Her mother, whos[e] maiden name was Nellie Robertson, was born in Guilford County, N.C., about 1766 and died in 1839... Children of Thos C::[eight in all]" included "Thomas P." The only further information relates to an older brother of Thomas P. Calhoun: an Alexander who moved in 1837 to Mississippi, where he farmed, taught school, and held some political office, and apparently was living in 1885.

The incongruity of the lists, as you see, lies in the fact that one has Samuel Calhoun born in 1740: the other represents its only Samuel as the son of Joseph, who was born in 1750. In view of the detailed character of my father's memo as regards his Samuel, I am inclined to accept that part of his account as at least a likely starting point for further inquiry. Beyond that I have no useful information.

Both I and later my brother Edward were graduated from Carleton College in Minnesota, I in 1915, he in 1923. Mother had managed to keep going by renting rooms on the second floor of our house to two young men, one a dentist, the other the passenger agent and dispatcher for the Great Northern railroad. My brother and I added what we could in part-time earnings. In 1916 Mother sold the place in St. Cloud, which had been her special project from the start. It stood above a valley that sloped down to the Mississippi River. We could see the river from an open second-story porch at the back of the house, screened for summertime sleeping and used often as an outdoor sitting-room. (When I was small, my father and I used to enjoy sitting out there during thunderstorms over the river. He could hear the thunder, and loved it.) Mother bought a small place in West Haven, while I continued study at Yale and my brother in the West Haven high school. On his eighteenth birthday, June 1, 1918, Edward left school (with his diploma) to enlist as a private in the army Medical Corps. He was mustered out as a sergeant in the summer of 1919, with a brand-new determination to study medicine, and enrolled at Carleton the succeeding fall. Mother sold the West Haven place, and went with Edward back to Minnesota. I spent 1919-20 in study at Oxford; continued work for a doctorate at Yale in 1920-21; went back to Carleton as an instructor during 1921-23; and all of us came back to New Haven in 1923, to live in rented rooms on Orange Street until Ella and I were married on December 24 and rented an apartment on Brownell Street. Edward was enrolled in the Medical School in 1923, and headed his class there until he developed a rapidly growing cancer in 1926, and died in April, 1927, a few days before Ted was born.

After Edward's death, Ella and I bought a two-family house in Westville, at 523 Central Avenue, so that there would be room for Mother to have rooms with us, and so that rental of the first floor could help toward purchase of the place. After Ted was born and with Bob and Harriet still to come, Mother lived with us during a part of her remaining years and part of the time in a small apartment around the corner on Willard Street. Her small income was cut in half during the depression of 1929-32, thanks to appallingly bad judgment on my part and to misguided brokerage advice. She endured more than one painful disappointment without complaint, and never blamed me for my share in increasing her hardship. She loved all the children, and they were I think fond of her, and she shared our family's life as far as she and we were able to share: exchanging visits and gifts, joining in our vacations, and so on. But without my brother, and with Ella busy with a growing family and I with a full-time job plus week-end engagements and summer teaching to help make ends meet, she spent some very lonely years until her death in the fall of 1933. She was living with us at the time. After a summer all together in Lisle, between Binghamton and Syracuse in western New York, Ella had gone with me to a conference in Colorado and developed an acute kidney infection that kept her in Mercy Hospital in Denver, while I returned to another conference engagement in Lisle. When that was over, Mother, the children and I returned to New Haven, and Ella was released from the Denver hospital to come home to rest with her parents and as it turned out to prepare for radical surgery to correct the disabling pyelitis. Meanwhile, Mother's heart was gradually failing, and in October, 1933, after a most unwise journey down three flights of stairs to the basement to stoke our coal-burning furnace, she managed to struggle back to her room but never walked again.

My father, mother, and brother are buried in a family plot in St. Cloud.

In 1942, Ella's father completed thirty years of service as a biochemist in the New Haven Agricultural Experiment Station. His eyesight had been falling for some time, but with friendly help from the staff, who were all fond of him, he had been able to set up experiments and have the results read off by better eyes than his. When he retired in 1942, Grandmother Wakeman's heart had been giving trouble, and it was evident that she could no longer carry the burden of independent housekeeping. It was then that with the help of Grandfather Wakeman's pension ($128 a month) and the income from a small list of investments, we sold our place in Westville (for about half what we had paid for it in the booming twenties) and bought Edwin Rudge's house and barns and about three acres of land in Bethany. Later, thanks to an appointment to a guest lectureship at the University of Chicago I bought the rest of Edwin Rudge's acreage almost 26 acres in all. As you know, Grandfather and Grandmother Wakeman had their home with us as long as they lived. Resale of most of the acreage, since my salary stopped in 1965, has helped to keep us afloat.

This has been written in spurts and stops during most of a week. Whether you will find it readable I don't know. It is obviously patchwork rather than a finished job. Maybe someday I can do better. But meanwhile this is about the best I can manage.

— Robert Lowry Calhoun, Family Notes: January 1978