Benjamin Toomer had been dead for over a decade when his youngest daughter, Lida Brooks (Toomer) Calhoun, and family made a trip to Mobile. His grave in Magnolia Cemetery, photographed during the visit, was a white headstone, readable in the photo. The current gravesite, added later, has a pair of large ledger stones, level with the ground. The first is inscribed to Benjamin Toomer and his wife Lucinda Huddleston. The second, his son, Edward Terry Toomer, and his wife, Anna Rambaut.

The other gravesite documented in the set of photos from this visit is quite different. I don’t expect the name of the person buried in this grave can be restored to its owner. I’m sure there are many people today who would like to know it.

![]()

![]()

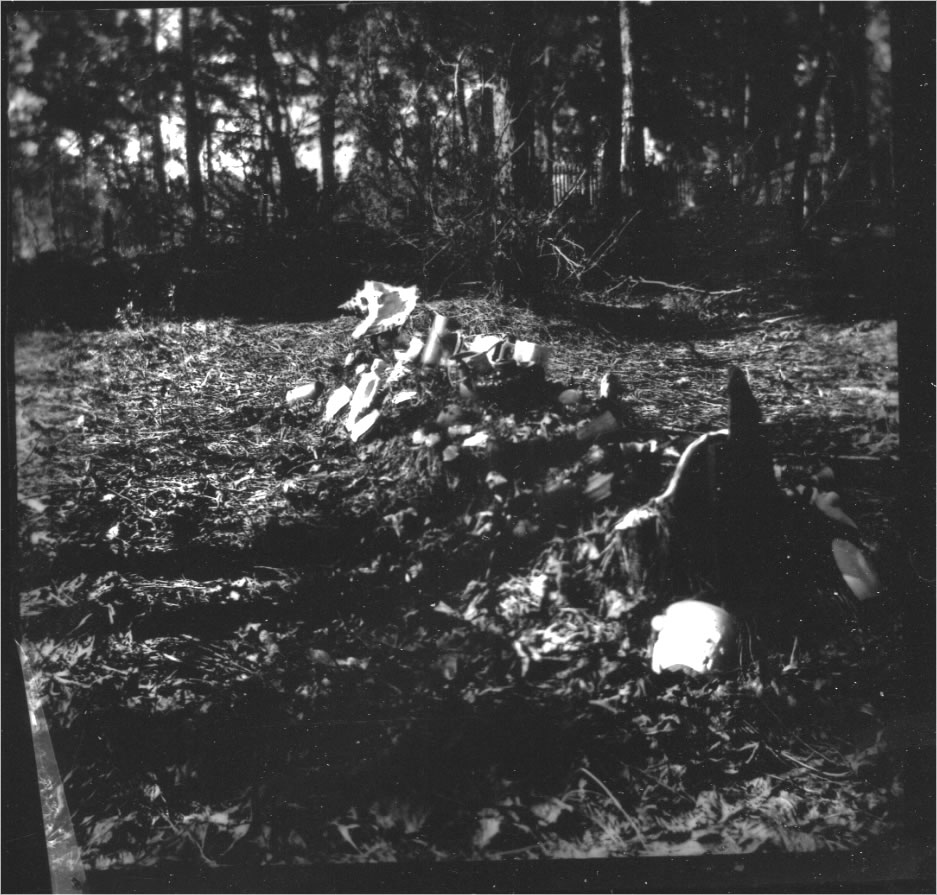

There may be a wooden gravemaker in the foreground—facing away from the observer. However, it’s only the other objects present that identify it as a grave at all. No other graves are observable and the surroundings are indistinct except for what appears to be a formal gate within the line of trees behind the site. Raised above the foot of the burial mound is a conch shell. Household objects are placed on top of the mound; several mugs, a pot, a figure that is, perhaps, a doll or a milk-glass flask. The clear, cultural context of these grave goods are as the ritual artifacts of 18th and early 19th century slave burials. The conch shell provided the soul with a safe vessel to make its transition to the afterlife, thought to be a watery place. The household objects were often the last touched by the departed soul and provided a medium for continued communication. By touching them, the living could occasion new contacts with the dead through dreams.

Recent efforts to acknowledge the place of the African-American contribution to the development of Mobile have resulted in the listing of the community known as Africatown in the National Register of Historic Places. Africatown was settled by the last slaves brought to America and their descendants. In 1859, long after it had been made illegal to import Africans as slaves, the ship Clotilda reached Mobile Bay but struck a sandbar. The Africans aboard were brought ashore on a riverboat and then distributed to the ship’s investors. Following the Civil War, freed slaves established their own community that became known as Africatown.

Observing Mobile today with the limited perspective of a Northerner who has never been there, it is a city reimagining itself in the present—with a renaissance plan for revitalization while preserving the significance of the past. There seems to be an honest effort to face squarely historical conflicts of race. This is evident in the African-American Heritage Trail, (prominent on the Mobile Historic Development Commission website), a tour and historic markers for everything from the slave market to Hank Aaron’s childhood playground. At the same time, friction remains. A bust of Cudjo Lewis, the last living slave from the Clotilda, was recently vandalized. Some wounds take longer to heal.

The cemetery at Africatown is included on the Heritage Trail. There are estimated to be over 3,000 graves, many of the oldest are unmarked. An effort in 2010 by the Africatown Archaeological Project with the resources of The College of William and Mary set out with ground penetrating radar to identify or at least delimit the earliest generations buried there. It is likely, but unknowable, that the gravesite in the photo is one that they plotted. Some closure for this wound would be welcome.

What was the relationship of my family to the slave buried in the loving manner of his own family and friends? Unless some new evidence is found in a forgotten box, we will never know. There is a passing chance that Lida knew who was buried there. Her father’s plantation was in Mauvilla, Alabama, the place where DeSoto fought the native tribe with that name—the origin of “Mobile” itself. For Lida, these were the idyllic days of her youth.

My mother's happiest years, almost certainly, were those of her growing-up time. She used to speak of her carefree country living now and again: her own horse to ride (side-saddle) every morning before breakfast; her own double-barreled shotgun to carry on quail hunts; her happy-go-lucky teen-age friends who swam in the Tombigbee, leaving a sentry on watch when a water moccasin had been sighted and had holed up in the river bank. On pic-nics there would be prime watermelons in wholesale lots sliced open for the heart, and the rest into the trough for the hogs. She remembered too teaching the children of the field hands to read, and helping to nurse them when they were sick. And she remembered the shock and sorrow in the South when the news came that Lincoln had been shot.

— Robert Lowry Calhoun, Family Notes: January 1978

Perhaps, the photographs raise too many unanswered questions for comfort. But, they seem to be the right questions. Creating an answer, giving due respect, healing the hurt of our past, may be what we must settle for at present.